By Tim Walker

Photo: Tony Rice; photo: Steven Dougherty

“Without courage,” the great Maya Angelou once wrote, “We cannot practice any other virtue with consistency. We can’t be kind, true, merciful, generous, or honest.”

We like to think of ourselves as courageous individuals, certainly. With little difficulty, we can imagine a dozen examples of behaviors that define courage, from soldiers in combat risking their lives to save fallen comrades, to a young LGBT student discussing his sexual orientation with his parents for the first time, to a small child bravely confronting a bully at school. But far too often, as a people, we tend not to act with courage, to take a risk. Too many times, we fall into step with the herd, or simply look the other way, or sit quietly when we should stand up and act.

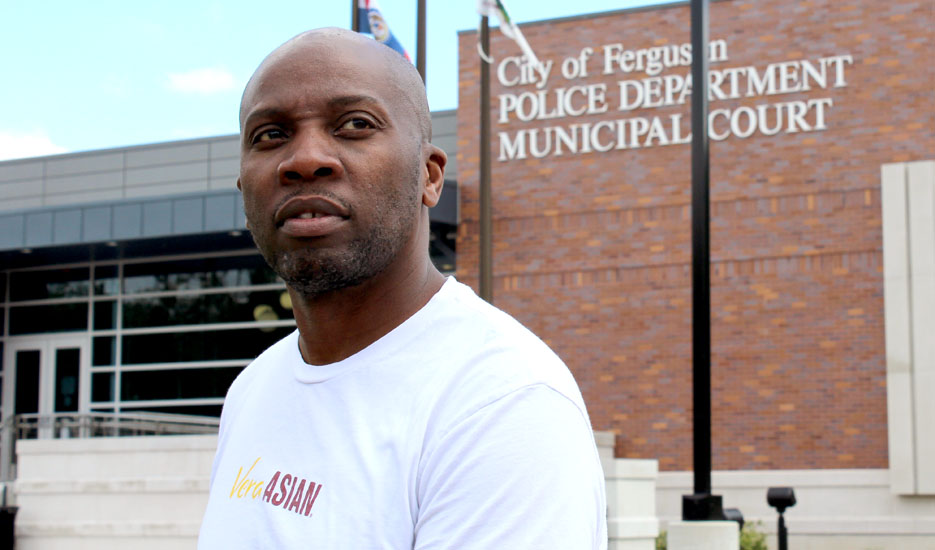

After the August 2014 shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, that city became the focal point for public protests against the unjustified use of deadly force by police forces nationwide against unarmed citizens. “Black Lives Matter” became a rallying cry for hundreds of protesters, many of whom marched on a nightly basis, who stood up and attempted to call attention to what they saw as a pattern of out-of-control police violence, violence that they felt was bloodying the streets of not just Missouri, but the entire nation. Some of them hit the streets and some of them stood up in other places, in other ways.

Should the actions of these people be considered courageous? Were they an example of “moral courage,” and if so, what specifically is “moral courage”? How would we best define that slippery phrase, and where then would we go to find good examples of it?

“Moral courage has always meant looking for those people that stood up,” says Joel R. Pruce, Ph.D., a professor of human rights studies at the University of Dayton. “People that, when faced with extraordinary crisis, really pitched in instead of looking the other way, instead of falling in with the crowd. Someone who really could not be a bystander to different kinds of abuse. That’s really what ‘moral courage’ is, at least for us. It’s the expression of a force in that individual’s experience when faced with these questions: Should I do something? Can I do something? And often, that requires taking on great risk, which is why the courage dimension can be very compelling in explaining that.”

An upcoming visual and audio exhibit at the University of Dayton hopes to capture and expand upon these ideas, and add important points of view to our national conversation on human rights, violence, and justice. “Ferguson Voices: Disrupting the Frame” is a photo and oral history exhibit running from Jan. 17 through Feb. 3 at the UD Roesch Library’s first-floor gallery. The project, a joint venture between the University of Dayton’s Human Rights Center and PROOF: Media for Social Justice, is free and open to the public. An opening reception, hosted by award-winning journalist and human rights leader Jimmie Briggs, will be held there Friday, Jan. 20, from 4-6 p.m.

The Ferguson exhibit emerged from the work of the Moral Courage Project, a team of nine UD students and three advisors who traveled to Ferguson, Missouri, between May 12 and 27, 2016. While there, the students, with Pruce, Briggs, and Leora Kahn acting as advisors, conducted an innovative oral history research project to preserve the stories of the people there who were affected by the Aug. 9, 2014 shooting of Michael Brown and the weeks of unrest that followed. Dozens of people were interviewed, and their stories preserved for posterity—stories about what life was like there before the shooting, during the unrest that followed, and afterward.

Unknown rebels

Making your voice heard. Standing up for what is right. Moral courage, obviously, is the strength to say and do what is right even in the face of your fears. A prime example might be Chinese man who, on June 5, 1989, one day after the Chinese government’s violent crackdown on the protests in Tiananmen Square, stood alone in front of a line of tanks, blocking their way into the square, his arms laden with grocery bags. The still-unidentified man, known worldwide as the “Unknown Rebel,” has become a powerful symbol of those who have the courage to stand up and be counted, whatever the risk. In Ferguson, hundreds of ordinary citizens found that same moral courage.

Kahn, a photo editor for 25 years and the founder and executive director of organization PROOF: Media for Social Justice, made the trip to Ferguson as an advisor for the group. “The Moral Courage Project really is about mobilizing students to be activists through the use of testimonies,” she tells Dayton City Paper, “and then also lifting up those voices that have the moral courage to step out of their usual roles in life and take a stand and do something. That’s really the essence of what this project is.”

When asked how she became involved with the Ferguson trip and the Moral Courage Project, Kahn responds,

“PROOF: Media for Social Justice sort of originated the idea about a moral courage project. And I’d actually shopped it around to several people at several different universities, and Dayton was really the natural for it because they have the Human Rights Center there. […] I couldn’t have imagined how transformative it would be for everybody involved. I knew that the students would get a lot out of it, but I don’t think Joel and I anticipated just how it would be so overwhelming for everyone—the students, and Joel and me and Jimmie Briggs, the facilitators, and the Ferguson people who participated. We went in there without a lot of expectations, and we got an enormous amount from everybody.”

Calling the project and Ferguson “really complicated,” Kahn says, “I think we did not understand what we were getting into until we actually got there. The whole reason for us to do the project was to find those positive stories, to find stories which [were]—the word I like to use is ‘transformative,’ because what we found were stories which transformed not only the people who were there taking the testimonies and reaching out, but also those individuals who were participating in the Ferguson protests and the aftermath. And for us, the whole reason for doing the project was to give voice to those people who were trying to make a difference in their community, and not just shouting about it and doing nothing. Every single one of these people who we interviewed were doing something, including this young girl, Valeri, who was 12 or 13 at the time. What she did, and in doing so risked a lot of her friendships, she went to the protests. She’s 12- or 13-years-old. So I think that, for me, hearing those stories and also seeing the students from Dayton really take ownership of the project [were transformative]. These students were very serious, very respectful, and I’ve done a lot of interviews in very difficult situations, and I was so impressed with these students, the respect, the research that they did, the questions that they came up with, and how they handled themselves in very hard situations. They were going into these people’s lives and asking them very difficult questions.”

With 35 local residents interviewed as part of the project, the students and advisors who were involved found themselves confronted with a vastly different picture of Ferguson than what had been portrayed in the national media. For many, it was an eye-opening experience.

“There’s a lot more to the story than people realize,” says UD student Steven Dougherty, one of the nine students who made the trip to Missouri to work on the project. “That was the biggest thing I got out of it. There are so many gray areas that lie between the black and white picture that the media painted of the area and the issues that surround it.”

“In my opinion,” Dougherty continues, “the national media just didn’t spend enough time with the story. It’s easy to look at something and say, ‘This is what happened.’ But it’s more telling to actually sit down with people […] for two to three hours at a time, and just have a conversation. And we found that painted a much more realistic picture.”

Jada Woods, another University of Dayton student whose work is featured in the project, agrees: “I think while I was in Ferguson, I did about 10 interviews of people, and not all of them were used because not all of them fit the moral courage umbrella—but it was still useful to hear their words and get their stories. It was all very inspiring. We’d had a class last spring that helped develop our skills further—interviewing skills, looking for moral courage, and we had a lot of hands-on training with people who did podcasts, and things of that nature. So, we had been doing that stuff, and with me being a communications major, I also had a background of interviewing people previously.”

Once the students who were participating in the project returned to Dayton and their classes in the fall of 2016, some of them started an independent study: they worked on transcribing interviews, editing audio recordings, and preparing material to be exhibited in a manner accessible to the public, all in anticipation of the January opening and a future website.

Briggs, who will be hosting the Moral Courage Project exhibit’s opening reception on Jan. 20, approached the project from a different perspective than the rest of the group.

“I actually grew up in the St. Louis area,” he tells Dayton City Paper. “For a period of my childhood, I lived in Ferguson, and my mom was a teacher there when I was younger. There were many years that I lived there, and ever since my childhood, Ferguson was always in my life. It was always a place that I knew, even when I wasn’t living there.”

Briggs worked along with Pruce, Kahn, and the rest of the cohort, joining them in Ferguson for most of the month of May 2016. Prior to his work on the Moral Courage Project, Briggs had already been traveling between Ferguson and his home in New York as he worked on an oral history book project about the city. He says that a large portion of the interviews for this project will be featured in the Voices of Witness book series, founded by author Dave Eggers, as well.

“I think it was critical that we did a good job,” Briggs states. “In the two years since Michael Brown was killed, I think the name ‘Ferguson’ has really come to invoke a cautionary tale of what communities don’t want to become, in the case of racial tensions around fatal police encounters. I think the narrative has lost this idea of who Ferguson really is, and who lives here. I think the students coming down, Joel coming down, Leora coming in, me being here, I think it just really made all of us, including the people we were engaging with… folks found that the community is much more than what it’s been portrayed to be in the national media.”

The opening reception of ‘Ferguson Voices: Disrupting the Frame’ takes place Friday, Jan. 20, from 4 – 6 p.m., and runs from Tuesday, Jan. 17 through Friday, Feb. 3 at the University of Dayton Roesch Library’s first-floor gallery, 300 College Park in Dayton. It is free and open to the public. Ear bud headphones and smartphones are recommended for the audio, but ear buds will also be provided at the event. For more information, please visit Facebook.com/MoralCourageProject, UDMoralCourageProject2016.Tumblr.com, or JPruce@uDayton.edu.

This story was originally published in the Dayton City Paper on 17 January 2017 (http://www.daytoncitypaper.com/disrupting-the-frame-35-ferguson-voices-break-from-the-national-narrative-at-ud/)